News >> Literature

09 Jan, 2013

09 Jan, 2013

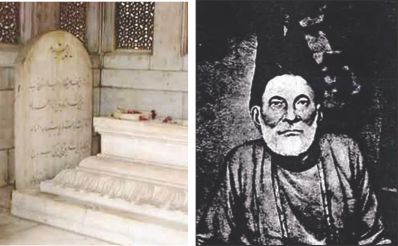

In the deadly sweep of every wave, said the poet Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib once, a thousand dangers lie in wait.

He would have known of those dangers, for he lived through them. Rising to poetic prominence in the fading glory of the Mughals, he was fated to witness the decay and decline of what had once been one of the most powerful dynasties not just in India but in the entire world as well. As his twilight approached, Ghalib watched the Mughal dynasty peter out, through the sheer power of British colonialism soon after the outbreak and subsequent collapse of the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857. The hapless Bahadur Shah Zafar, emperor-poet, of whose munificence Ghalib had partaken of, was removed to Rangoon after a humiliating trial at the hands of the colonial power. It was in Rangoon that the heart-broken emperor would die. The British were determined that nothing remained of him and one way of ensuring that was to spray acid over the corpse of the emperor and so make sure his remains would quickly mingle with the soil in his grave.

In post-1857 Delhi, Ghalib, like so many others, most of those others being Muslims of all categories, was swiftly pushed into leading a forlorn existence. The pension granted to him by the Mughals was stopped and no matter how much he went from one colonial door to another seeking its reinstatement, nothing happened. None of his petitions moved the hearts of the new rulers. Ghalib, like so many poets of his generation, had never worked for a living but lived on the largesse of his benefactors, chief among whom was Bahadur Shah Zafar. Within days of the fall of Delhi, the poet was hauled before a young British military officer, who wanted to know if Ghalib was a Muslim. Half, said the poet in response. To the consternation of the officer, Ghalib informed him that he drank wine but ate no pork. Even in his state of misery, Ghalib was capable of making a facetious statement.

And yet Ghalib's place in the literary history of the Indian subcontinent rests on the melodious nature of his poetry. In our times, we have remembered Ghalib chiefly through his ghazals, notably those that came to be popularized in the movie that carried his name. Talat Mahmood and the actress-singer Suraiya made the poet's 'dil-e-nadaan tujhe hua kya hai' famous through their rendition of it in the movie. And then, of course, were such other numbers, in the movie and outside in a plurality of voices, as 'ye na thi hamari qismat ke visaal-e-yaar hota'. This ghazal has been sung to different modulations by such artistes as Suraiya and Pakistan's Habib Wali Mohammad. Today, close to a hundred and fifty years after Ghalib's passing, ghazals are the standard by which one judges the poet, which indeed have accorded him the pre-eminence he enjoys in Urdu and Persian poetry today. Ghalib knew both the languages well, along with Arabic. In his youth, it was Persian he employed as the language of his poetry. But then came the switch to Urdu, a move that was to enrich the language in ways never foreseen earlier. The ghazals continue to be sung to undying appreciation. The recently deceased Jagjit Singh was one of the few artistes who gave fresh new life to Ghalib through his focused rendition of the ghazals. The depths of passion that Ghalib could call forth in his poetry were emotions which Jagjit captured marvelously well in such songs as 'wo firaaq aur wo visaal kahan / wo shab-o-roz wo mahosaal kahan'. Nostalgia strikes him and you feel, vicariously, the profundity of his loneliness in a world not his any more.

And loneliness it was in Delhi once the British took over. An entire city was razed to the bare ground, with not even trees and other forms of greenery spared. With the defeated soldiers and followers of the fallen emperor placed on summary trial, followed by hasty executions, Delhi quickly turned into a city of fear. Never before in history, except perhaps in medieval times, had the fortunes of a people so briskly been laid low. Nothing was, a sentiment which is felt in Ghalib's elegiac 'na tha kuch to Khuda tha / na hoga kuch to Khuda hoga'. Or feel the pain in the sad lamentation:

'An ocean of blood churns around me / Alas! Were these all! / The future will show / what more remains for me to see.'

Of Ghalib's family we know hardly anything. He is said to have married at thirteen but then marriage could not keep him within its strict confines. He sired seven children, all of whom died before they could grow into adulthood. He was deeply attracted to women, and they to him. It is thought that he had at least one serious romantic liaison in his life, a phase which certainly must have given a spurt to his poetry. Religion, in that conventional sense, had little appeal for Ghalib, seeing that his poetic instincts regularly came from his drinking. Or you could suggest that the Muse in Ghalib was awakened through a mystical union of saqi and sharabi. If, as Ralph Russell once noted, Urdu poetry is meant to be recited and not read, then Ghalib's poetry was not merely recited but, on a more elevated level, transformed into soulful music. Recall the following:

'Muddat hee hai yar ko / mehmaan kiye hue / josh-e-qada se bazm / chiraghaan kiye hue . . .'

Which, in Russell's translation, stands thus: 'An age has passed since I last / brought my beloved to my house / lighting the whole assembly /with the wine cup's radiance'.

Those among you who have heard Noor Jehan sing this number half a century ago, or more, will yet feel the bitter-beautiful pain inherent in the parting of loving man from beloved woman.

Ralph Russell, the British scholar in Urdu literature, made it his particular vocation to study Ghalib in all his manifestations. That includes Ghalib's letters, which have down the years been regarded as a masterly presentation of the epistolary form in Urdu. Russell made extensive tours of India and Pakistan while researching Ghalib, a job he finished to satisfaction through his rich work, The Oxford India Ghalib, published by Oxford University Press. And then of course there has been Pavan K. Varma, whose Ghalib The Man remains a necessary account of the tumultuous life the poet led, with special focus on the troubles he continually came up against after the disaster of 1857.

As for Ghalib's own works, there is the Diwan-e-Ghalib, published in 1841, followed by Panj Ahang, a handbook essentially on the writing of letters and poetry published in 1849. A more poignant work remains, of course, his Dastanbui, an account of his experiences following the collapse of Mughal rule in India that he produced eighteen months after the traumatic events of 1857.

Ghalib's haveli at Gali Qasim Jaan, Ballimaaran, in Old Delhi is where the poet spent the last years of his life. It is today a museum, home to poetry enthusiasts grateful to Ghalib for the exquisite nature of his poetry. And the poetry rested on love, all the way:

'Love knows no difference between life and death / the one who gives you a reason to live / is also the one / who takes your breath away . . .'

Jawaharlal Nehru, having watched the movie 'Ghalib' (1954), was in his element as he told a happily surprised Suraiya: 'You have put life into the soul of Mirza Ghalib.'

(Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib was born on 27 December 1797 and died on 15 February 1869).

Source: daily star